Culture

Shikyntien Kwai: A Folklore about Betel Hospitality in Khasi Society

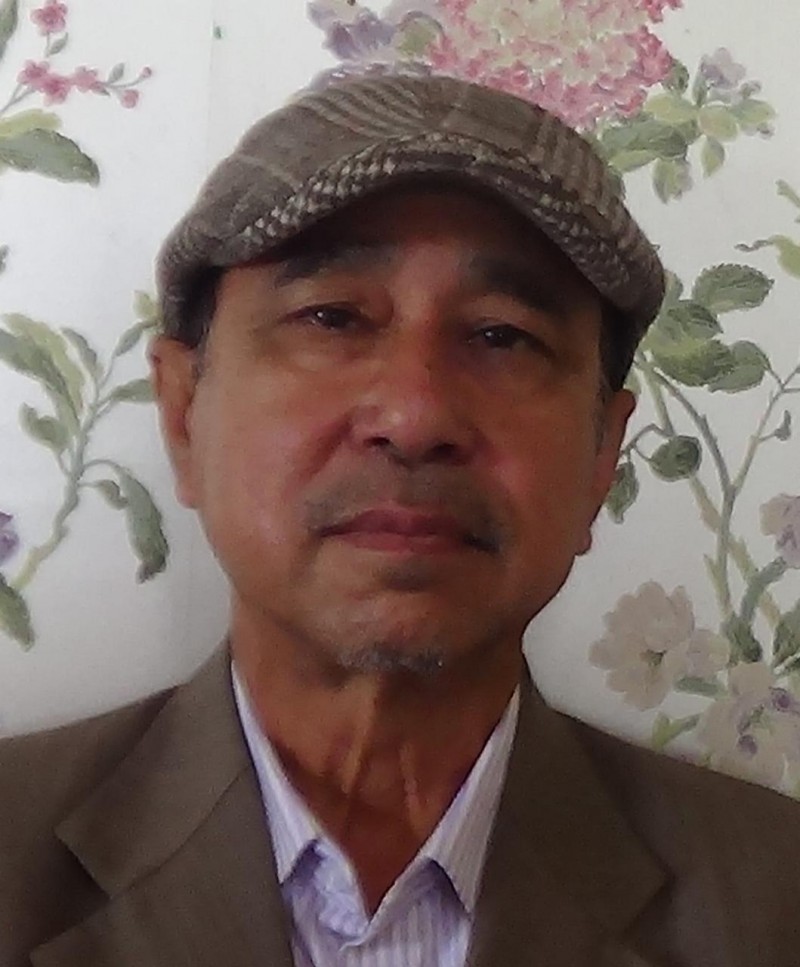

Current Updates | Culture | Philip Lyngdoh | 14-Oct-2020

Once upon a time, in the idyllic village of Rangjyrwit that perched daintily on a beautiful hill slope, lived two bosom friends, Nik and Shing. They were companions since childhood and remained inseparable even after they married. Nik came from a rich and influential family of merchants and also married into a rich household. Shing belonged to a family of poor daily wagers, who eked out their living by doing odd jobs and his wife too came from the lowly working class. But the wide difference in social status and wealth never dented their deep and steadfast friendship even one bit. As young boys, Nik and Shing always roamed the fields and forests together, swam and hunted together. As adults, although engaged in their own occupations, they still met and kept in touch whenever they could. Soon Nik had to take over his father’s business and remained away most of the time. Even so, whenever he was in the village the two friends would meet at his house.

Several visits later, Shing’s wife said to her husband, ‘You always were the one to visit your friend at his house, isn’t it about time you call him to ours at least once?’ Shing agreed that it was indeed selfish of him never to have invited his friend over. So one day he asked Nik to visit his humble dwelling and have a meal together, never mind even if that wouldn’t be a sumptuous feast. Nik accepted the invitation and turned up unannounced one day at their door. Shing and his wife were overjoyed to see him. As they sat and talked, Shing’s wife went to the kitchen to prepare something. But it so happened there was nothing to offer, not even a grain of rice. She peeped through the door and signalled at her husband to come. ‘There’s no rice at all, and no fish too’, she said, a cloud of worry writ large on her face. Shing was alarmed, ‘Go and borrow from the neighbours for a measure of at least a meal so we can offer our friend’, he told her.Shing’s wife went but soon returned empty-handed. ‘None of the neighbours would give even half a measure of rice’, she said.

The new situation devastated Shing. Fate had struck a cruel blow. He couldn’t offer even a small morsel of food to his only friend for the first time in his life! Even the neighbours are so unkind as to not lend them a cupful of rice. Stricken with hopelessness, shame and grief Shing concluded that it was better to die than to live such a miserable existence. Thereupon he took the kitchen knife and stabbed himself. Shing’s sudden action shocked his wife beyond belief. She saw no reason to live, especially now that her beloved husband had gone. With the same knife, she too took her life. As an hour passed with no sign of his friends and no sound from the Kitchen, Nik began to wonder. The sun soon went down too. Curious, he stepped into the kitchen and saw a gory sight that stunned him into stupefying horror. Two bodies lay sprawled on the floor, drowned in their own blood. The water was simmering in the pot over a dying fire. There was no rice in the basket, no fish, and no vegetables in the larder.

It didn’t take long for Nik to realise what had happened. Shing and his wife had taken that extreme step because they were so ashamed they had nothing to offer him on his first-ever visit to their house. Intense remorse engulfed Nik. What grieved him most was his failure to realise how much in want his friend was. Now it was impossible for him to offer any help. With his bosom friend gone forever into the other world, life on earth held no more meaning for him thenceforth. It was better he joined him rather there than live an empty life alone, he reasoned. He too, took his life with the same knife.

As darkness steadily stole in, a dark silhouette scampered towards the house. There was a thief who was running to escape from a posse pursuing him. Espying the open door of Shing’s hut, he huddled in a corner, listening for sounds from inside. He heard no nothing, no sound, and no noise. I will be safe here, he thought. Furtive as a mouse he entered the house, into the corner-most area, of the kitchen, to hide till the commotion outside subsided. Meanwhile, he fell into a deep slumber. The sun was already up when he awoke to the horrifying scene before his eyes. Fear and panic gripped him like a vice. ‘I’m certainly done for now’, he said to himself, ‘Oh, woe is me! Surely people will now pin me for murder too!’ The thief saw only one escape route. He too stabbed himself to death.

As the day progressed the neighbours began to notice that something was amiss – the open door, the silence within. They entered the house to be greeted by a gruesome sight of four dead bodies lying in pools of coagulated blood. Shocked and bewildered, they tried making sense of the tragedy. They soon understood why the friends and the thief killed themselves. Grief and shame overcame them. Had they helped the poor couple such a sad event could have been avoided. So to make amends they started the tradition of offering ‘shikyntien kwai’ – serving of kwai – as a courtesy to any guest who visits a house. ‘Shikyntien kwai’ is so affordable that even the poorest of the poor can offer. So when you enter a Khasi home or even meet a Khasi friend on the road don’t be surprised if you’re offered a ‘kwai’. It’s a gesture of Khasi welcome in remembrance of the three friends – and the hapless thief - who took their own lives and gave the Khasi people this unique tradition of hospitality. In this folklore, the kwai (betel nut) symbolises Nik the steadfast friend. The betel leaf (tympew) with a dash of slaked lime (shun) on it symbolises Shing and his wife who are always together. The fourth ingredient, tobacco (dumasla), is rarely taken but if so, stays tucked in the corner of the mouth just like the thief in the kitchen corner.

(The Author is a retired Sr. Asst. General Manager of Air India. He can be reached on philip.lyngdoh@gmail.com. Story narrated is from his personal knowledge)

Leave a comment